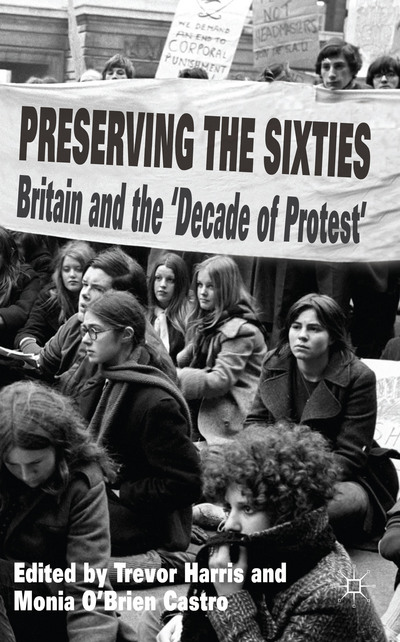

Review of Preserving the Sixties. Britain and the ‘Decade of Protest’, Edited by Trevor Harris and Monia O’Brien Castro, Basingstoke : Palgrave Macmillan , 2014. 197 pp. (xvi p.). ISBN 978-1-137-37409-.

Do the Sixties need to be preserved? Surely, the cultural legacy of that decade speaks for itself and the current revival of Sixties style in fashion and interior design, not the mention the perennial impact of pop culture and music on the cultural scene fifty years on, are evidence enough that preservation is assured.

This collection of essays examines the political culture and the politics of culture in Britain during that iconic period. Eleven contributions by British and French academics are arranged into two general sections under the heading of politics and culture, a choice which may seem somewhat artificial, given the interchangeable nature of the two headings. Following three introductory pieces – the thought-provoking Foreword by Dominic Sandbrook, the Introduction by the editors, and a historiographical overview by Mark Donnelly, the chapters progress broadly from political science and historical to the cultural studies approach, but all contributions inevitably deal with both, the Sixties being defined by their cultural imprint. The themes and specific topics covered range through political organization and legislation (Industrial relations, abortion), political groups and culture (radical left, Northern Irish civil rights) cultural expression of political protest (satire, music, fiction). Inevitably notions of counter-culture, liberation, youth, modernity are evoked and definitions proposed.

A definition of the ‘Swinging Sixties’ is first suggested by the first three pieces (Sandford, O’Brien Castro & Harris, Morris). The idea that the hip counter-culture was a mass phenomenon is countered, only relatively few experienced the inner sanctum of the ‘chic’, ‘in’, ‘with it’ circles. Yet not only dress and music, but also education, technology and consumer goods underwent massive transformation in this period and there was undeniably a liberalization of mores and a democratization of access to culture.

The circumstances and consequences of the 1967 abortion law (Pomiès-Maréchal and Leggett), industrial relations legislation (Chommeloux), the situation in Northern Ireland that lead to Bloody Sunday (Pelletier), are examined with reference not just to the political and social setup, but also to cultural and social representations at the time and subsequently. For example, the complicated links between the Radical Left (Communists, International Marxists, International Socialists, Socialist Workers Party) and popular cultural icons John Lennon and Mick Jagger (Tranmer) reveal that simplistic categorization does justice neither to the singers nor the left-wing political groups.

The final section provides a close reading of several iconic cultural artefacts, the Beatles’ White Album (Winsworth), the Kinks’ songs (Costambeys-Kempczynski), the Monty Python television show and the weekly satire TW3 (That Was The Week That Was) (Roof), or again emblematic poetry and novels (Vernon) or the work of playwright Brian Friel (Pelletier).

The multiple contradictions of the Sixties are highlighted. Several pieces underline the underlying tensions between consumerism and the critique of consumer society via music and television (Winsworth, Roof), or the opposition between individual freedom and state or collective action (Vernon), indeed the oxymoron ‘collective laissez-faire’ is used to describe industrial relations at the time (Chommeloux), or again the generational confrontation between the hedonistic culture of babyboomers with its accompanying ideals of enduring halcyon and their parents’ war-weary, unselfish and upright posture of dignity and fortitude at all costs (Donnelly, Winsworth, p.160, Morris, p.33). The book confirms the antagonisms between conservative traditionalists in the Labour party supported by its traditional and traditionalist working-class electorate (Pomiès-Maréchal and Leggett, Tranmer), shunning popular culture and long-haired idols, and the liberal permissive intelligentsia whose idea of what constituted ‘civilized’ behaviour (p68-69) was to lead to social reforms that the former disapproved of (such as the decriminalization of homosexuality and abortion).

Similarly the Sixties were an era of unbound optimism and unlimited growth and the wholesale rejection of the past, when ‘modern’ became a by-word for a tabula rasa in architecture and town planning, bulldozing historic landmarks, when a ‘major reordering of space’ (Morris) aimed at rationalizing haphazard higgledy-piggledy development in towns and homes and the railways (the Beecham Axe) – concrete jungle versus rural idyll, before the setting in of an awareness that the aesthetic and functional arrangements of previous eras had some value, reinstating nostalgia for the steam train, the trunk line, the village green (Costambeys-Kempczynski).

The essays also attempt to place markers at defining moments which flag the beginning and end of this era, and to replace the decade during which visible social change was manifest, in a longer time-scale. The decade or so of The Sixties is defined in terms of the economy and industrial relations as a period of transition between post-war orthodox interventionism under the portmanteau term of Butskellism and post-modern neo-liberal Blatcherism (Chommeloux). In cultural terms, the modernism of the Sixties pop music and mid-century modern architecture for example, gave way to punk and neo-eclectic post-modern architecture. The Sixties were accused of being the cause of all subsequent evils: capitalism and consumerism, welfare dependency, technology and multinationals, and yet, as Donnelly points out, they were also a period of collective protest, state surveillance, of a revolution in the mind (Hardt & Negri, Empire, 2000).

The bibliography at the end of each chapter give indications for further reading, whilst the index provides a useful, though incomplete, number of entries into the text. The Fab Four are all indexed but not Roy Jenkins, Edward Heath but not Bernadette Devlin, Bloody Sunday, NICRA (Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association), the CRA or the CDU (Campaign for a Democratic Ulster). The index does reveal however, by way of the number of entries under these headings, two polysemic and frequently used terms from the period, typical of the discourse and preoccupations of the period: class and revolution. Perhaps these notions could have been examined in a specific chapter each, especially as the subtitle of the book is Britain and the ‘Decade of Protest’.

This collection is an excellent survey of a number of phenomenon whose roots stretch back not only to the 1950s but to pre-Second World War Britain, a picture not only of the Sixties, but of Britain in the mid-twentieth century, following the hiatus and upheavals of the war. To determine whether they are to be considered as the end of a forty-year period (1930-1970) or a prelude to the next forty years (1960-1997) would need a wider lense.

Royaume-Uni : débats et dissension, Paris: SEDES, 2009

Royaume-Uni : débats et dissension, Paris: SEDES, 2009 quand Liverpool prit son essor, figure à plusieurs reprises dans les récits : comme point d’entrée d’une population noire, esclaves ou hommes/femmes libres (Dresser), comme plaque tournante de la traite triangulaire (Satchell), comme lieu privilégié d’enquête par Thomas Clarkson (2) et comme centre actif d’un noyau d’anti-esclavagistes dès 1787 (Whelan), et d’action militante – le poète romantique Samuel Taylor Coleridge, qui affectionnait les séjours dans le Somerset et le Devon au sud de Bristol, y donna une conférence anti-esclavagiste en 1795 (Kitson).

quand Liverpool prit son essor, figure à plusieurs reprises dans les récits : comme point d’entrée d’une population noire, esclaves ou hommes/femmes libres (Dresser), comme plaque tournante de la traite triangulaire (Satchell), comme lieu privilégié d’enquête par Thomas Clarkson (2) et comme centre actif d’un noyau d’anti-esclavagistes dès 1787 (Whelan), et d’action militante – le poète romantique Samuel Taylor Coleridge, qui affectionnait les séjours dans le Somerset et le Devon au sud de Bristol, y donna une conférence anti-esclavagiste en 1795 (Kitson).