Le projet de recherche en lien avec le Fonds Dubois au SCD de l’Université de Poitiers, « Early 20th century economic history book collectors and their collections : Herbert S. Foxwell, 1849-1936 », soumis à l’Ambassade de France à Londres et à Chuchill College Cambridge, m’a valu l’honneur d’être nommée Overseas Fellow de Churchill College, où je mènerai ce projet de janvier à juillet 2021.

Ci-dessous le projet soumis (en anglais):

The comparative & interdisciplinary ongoing research project focuses on issues of collection formation and the sourcing of rare economic history books with reference tosignificant collections and collectors. It throws light on networking and nodal connections in the world of antiquarian books and academic scholarship in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This part of the project centres on the life, workand collections of Herbert S. Foxwell (1849-1936) Fellow at St. John’s between 1874-1889 and 1905-1936, and Professor of Economics, University College, London.

According to J.M.Keynes, the collections Foxwell sold to Harvard ‘should rank with the GL [Goldsmiths’ Library] in London and the Seligman collection in Columbia as one of the three outstanding economic libraries in the world’ (1), making Foxwell, responsible for two of the three, the foremost collector in the field.

[Photo : Keynes & Foxwell’s neighbouring houses in Harvey Rd., Cambridge]

Today, Foxwell’s collections at Senate House (Goldsmiths) and the Baker Library, Harvard Business School (Kress Collection of Business and Economics) together form the Goldsmiths’-Kress Library of Economic Literature, composed of 60.000 monographies from before 1850, reproduced on microfilm in the 1970s, and now an online subscription-based corpus which has recently been given digital humanities research tools.(2) Keynes called this corpus ‘Foxwell’s main life work and his chief claim to be remembered’. (3) Foxwell’s collecting and cataloguing set standards for the range and breadth of subjects and the methodological tools for economic history source description.

The collective corpus collated by five eminent collectors active in the period 1880-1930 (4) forms the largest privately-constituted depositories of works in the field of early economic history outside public institutions such as the British Library and the National Library of Australia. Major disposals of private librairies in country houses in Britain led to acquisitions of books by learned (and monied) private collectors, and, through subsequent donations and acquisitions of whole new collections, to significant depository holdings on economics in academic librairies in Britain (Senate House Library), the United States (Columbia & Yale Libraries), and The Netherlands (International Institute of Social History). The five collectors comprised one Frenchman, two Englishmen and two Americans. Three of them held chairs in economics: Auguste Dubois (1866-1935) at Poitiers from 1908, Edwin Seligman (1861-1939) at Columbia from 1904, and Herbert S. Foxwell (1849-1936). All three were instrumental in the emergence of their discipline, founding associa tions and journals for the study of economics, and supporting institutional initiatives.

tions and journals for the study of economics, and supporting institutional initiatives.

At Cambridge, ‘the struggle to establish Political Economy as a subject in its own right’ led to a specific economics department collection in 1906, with Keynes as Librarian.(5) Foxwell was founder member of the Royal Economic Society and the Economic Journal (1891-).Seligman was the editor of the Political Science Quarterly and founder member of the American Economic Association. Dubois co-founded the Revue d’histoire des doctrines économiques et sociales (1908-1912) – Revue d’histoire économique et sociale (1913-1977). The fourth collector, Henry R. Wagner (1862-1957), collected and catalogued rare books in the field. The fifth, one of their principal suppliers, was Leon Kashnor, a specialist antiquarian book dealer, sold collections to the International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam in 1937 & the National Library of Australia (Canberra) in 1950.(6)

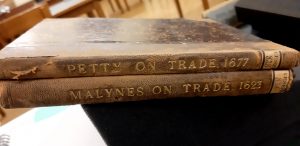

The University of Poitiers Manuscripts & Rare Books Library holds the prestigious Dubois collection composed of around 6,000 works on political economy published between the 1670s and 1840s, with a number of extremely rare pamphlets, including a previously unexplored & unrecognized depository of around 900 early English titles (1560 to 1840), bequethed to the University in 1935 by August Dubois, Poitiers Professor of Economic & Political Doctrine. Fonds Dubois: ouvrages en langue anglaise, traduits de l’anglais ou publiés en Grande-Bretagne [PDF -439Ko]. Having recognised the significance of this deposit, I have been researching and promoting itthe past ten years. To date, 50,000€ has been awarded on competitive merit by international and French national and regional research institutions for the project. Thematic exhibitions have been held : The State of Ireland 1640-1830 (2015), 1688 The Glorious Revolution (2017, web publication forthcoming). A number of works in the collection have been digitalized in their entirety for the virtual library on early Utopian socialists. I have published articles, given papers, and organised conferences around this collection. I set up an international network comprising over forty academics and twenty institutions including Brown, Columbia, Yale, Harvard,London, Sheffield, Leeds, the Sorbonne, Montpellier, the EHESS (Paris), which, it is hoped, will be extended to include Cambridge as a result of this project, http://dubois.hypotheses.org/. These serve as a link between the different fields and researchers. In 2020, the European Early American Studies Association (EEASA) is holding its bi-annual conference in Poitiers as a result of interest generated in the Dubois collection.

Two previous visiting fellowships at Yale, 2014, and at the Huntington Library, California, 2017, provided support for studying firstly the collection of 6,000 items donated to Yale (Beinecke Library) by Henry R. Wagner; the collections bought from Herbert S. Foxwell (1849-1936) by the Baker Library, Harvard Business School, and the Hugh Bancroft (1879-1933) collection; the Seligman Papers and 50,000 item collection at Columbia University Library.

The web of collectors of economic history rarities and the provenance of a numberof books in these collections, bought from antiquarian booksellers in London, Leon Kashnor (Museum Bookstore), was established and I began to map the links between purveyors and collectors of rare economic tracts in London in the 1890s to 1930s. The William Reece Fellowship (Huntington), was dedicated to work on H. E. Huntington (philanthropist, collectioner) and H. R. Wagner (silver dealer & book collector in London in the 1910s), and antiquarian booksellers they dealt with. Wagner, like Foxwell, was a dedicated bibliographer. His Irish Economics:1700-1783, (7) was privately published in 1907. A bibliography of British economic tracts was never completed.(8) In the common pursuit of identifying and locating as many early works on economic history as possible at a time when their value in monetary terms and the profile of economics as a discipline were low, Foxwell, Seligman, Wagner and Dubois were aware of their peers, as collectors and academics and, from 1911 at least, (9) exchanged bibliographical information, and lent each other books, catalogues and index cards in an ongoing transatlantic conversation.(10)

This project proposes to further examine and revalue Herbert S. Foxwell’s book collecting, his unique contribution to the preservation of rare pamphlets & the bibliography of economic history and his status in the emergence of the Cambridge school of economics (11) in a wider perspective. His work ‘heavily influenced Edwin R.A. Seligman’ (12) and ‘testified to the “global exchange of knowledge” in the late nineteenth through early twentieth centuries’ (13) between a small but influential group of academics & bibliophiles on both sides of the Atlantic, whose expertise, connexions, flair and dedication, remain largely unrecognised.

Foxwell acquired over 50.000 items over his lifetime. (14) In 1901, at the age of 52, to finance and make room for further acquisitions, he sold a collection of 30,000 items to the Goldsmiths Company. It was deposited with the University of London in 1903. Both Cambridge University Library and the LSE had been interested in acquiring it. Seligman also showed an interest.(15) In 1929, a collection of duplicates was sold to Harvard. After his death, a collection of 20,000 volumes was acquired by Harvard with the help of C.W. Kress. Foxwell’s dispersed collections arethus now reunited in The Goldsmiths’-Kress Library of Economic Literature, 1450-1850, virtual online collection The Making of the Modern World. (16) I have already been able to consult the deposits at Senate House Library, London and the Baker Library Historical Collections,Harvard Business School. Further papers of Foxwell’s are held by the Kwansei Gakuin University Library (Japan)and are consultable online. During the Fellowship period, I intend to explore archival material and libraries at a number of Cambridge institutions: the Marshall Library of Economics (the papers of H. S. Foxwell, J. M. Keynes, Alfred Marshall (17), James Bonar, Austin Robinson, Charles Rye), Cambridge University Library, for additional archive material (letters from or to Foxwell, work by him, information concerning his correspondants and contemporaries) and the libraries of Churchill College (Robinson), St. John’s (Foxwell, Larmor, The Eagle), King’s (Marshall, Keynes, Pigou, Browning), Trinity (Edward E. Foxwell, Sidgwick), Magdalene and Sidney Sussex.

The history of these collectors and collections (provenance, acquisition, cataloguing, dealings with antiquarian booksellers) and the selection of the works deemed worthy of inclusion informs research in cultural studies : the book trade and the antiquarian market; the value/scarcity or popularity of works on political economy; philanthropy, academia, and bibliophilia in ‘fin de siècle’ London; the development of economics as an institutional and academic discipline. It also contributes to the archeology of economic concepts, epistemological debate, and the role of academe in preserving such artefacts. This research in Cambridge on Foxwell’s collecting and compiling, sourcing and cataloguing of rare economics books will enable several work-in-progress papers, and a book project, be completed and submitted for publication following this Fellowship.

1. J. M. Keynes, C. E. Collet, [obituary] « Herbert Somerton Foxwell, » The Economic Journal, Dec. 1936.

2. John J. McCusker, « An Introduction to The Making of the Modern World. » The Making of the Modern World. Detroit, Gale Cengage Learning, 2011.

3. J. M. Keynes, Essays in Biography, The Royal Economic Society, Palgrave Macmillan, (1st ed. 1933), 2010, p.238.

4. Other collections were constituted later: Kansas Howey Economic History Collection, Hitotsubashi University Li-brary, Tokyo.

5. Marshall Library of Economics. Origins.

6. Huub Sanders `Books and pamphlets on British social and economic subjects (ca. 1650-1880) at the IISH Amsterdam’, 1988; The Kashnor collection : the catalogue of a collection relating chiefly to the political economy of Great Britain and Ireland from the 17th to the 19th centuries, Canberra, National Library of Australia, 2 Vols., 1969.

7. Foxwell considered the title to be exaggerated, as half the titles concerned money and banking. Letter to W. R. Scott, July 1, 1931, H.S. Foxwell Papers. Baker Library Historical Collections. Harvard Business School.

8. Boxes of typescripts and index cards, Henry R. Wagner Collection, Beineke Library, Yale; m/s Bibliography of Brit-ish Economics, 1499-1799, UCLA Special Collections.

9. Columbia University, Rare Books Manuscripts Files, MS Coll Seligman, Letter Foxwell to Seligman, 4 June 1911.

10. Columbia, MS Coll Seligman, Letter from Seligman to Janet Bogardus, Librarian of the Seligman Collection at Columbia, 7 September 1936; Janet Bogardus, to Frank W. Fetter, Haverford College, June 14th 1937;Frank W. Fetter, Haverford College, to Janet Bogardus, 16 February 1938.

11.Peter Groenewegen,The Minor Marshallians and Alfred Marshall: An Evaluation, Routledge, 2012; Rogério Arthmar & Michael McClure, ‘Herbert Somerton Foxwell (1849-1936), in Robert A. Cord (ed.), The Palgrave Companion to Cambridge Economics, Springer, 2017.

12. McCusker, ‘An Introduction…’, 2011.

13. Foxwell papers, Kwansei Gakuin University Library.

14. Anon [Keynes]. ‘Professor Foxwell; The Bibliography of Economics,’ The Times, Aug. 4, 1936; .J. M. Keynes , C. E. Collet, « Herbert Somerton Foxwell, June 17, 1849-August 3, 1936, » The Economic Journal, Dec. 1936.

15. Letter from Foxwell to Seligman, letter dated 22 July 1901. Columbia University, Rare Books Manuscripts Files, MS Coll Seligman.

16. The Making of the Modern World. Detroit: Gale Cengage Learning; J.H.P. Pafford, “Introduction” in Canney, M., Knott, D., Catalogue of the Goldsmiths’ Library of Economic Literature,London: Cambridge University Press, 1970-1995, vol. 1, pp. ix-xxi.; Jeffrey L. Cruikshank, A delicate experiment: the Harvard Business School, 1908-1945. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press, 1987; Senate House Library, University of London, ‘Herbert Somerton Foxwell and the Goldsmiths’ Library: A Brief History’; Peter Groenewegen, ‘Alfred Marshall and Henry S. Foxwell. A Tale of Two Libraries’ in Classics and Moderns in Economics, Essays on Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Economic Thought, Vol. 2, Routledge, 2004, pp.72-85.

17. The Correspondance of Alfred Marshall, Economist, edited by John K. Whittaker, CUP, 1995.

A paraître dans The Book Collector, Vol. 74.4, Winter 2025, ‘The smartest bookseller in London’ Leon Kashnor (1879–1955) and the Museum Book Store’.

A paraître dans The Book Collector, Vol. 74.4, Winter 2025, ‘The smartest bookseller in London’ Leon Kashnor (1879–1955) and the Museum Book Store’.